This book, Pictorial Composition and the Critical Judgment of Pictures, by Henry Rankin Poore and written in 1903 is one of the most brilliantly written books I have come across. It is a subject about which many artists lack knowledge and thus struggle with their work, simply because it was information they were never taught. The book was originally written in 1903 and was written with a more eloquent and decorative speech, which many folks may find difficult to wade through. I will be attempting to translate the dialogue in the book into something you may find easier to read – hopefully without losing too much in the translation. It is a book you can find on-line or as an E-book. Some of the pictures he references in the book I will try to re-source since the scans of the original may be suboptimal to observe what he is talking about.

CHAPTER III – BALANCE

Of all pictorial principles none compares in importance with Unity or Balance.

Of all pictorial principles none compares in importance with Unity or Balance.

“Why all this intense striving, this struggle to a finish,” said George Inness, as, at the end of a long day, he flung himself exhausted upon his lounge, “but an effort to obtain unity, unity.”

Someone who watches an artist at work at his easel will notice how the artist is always trying to see his work in a novel and unusual way. He’ll reverse the image in a mirror, turn it upside down, view at different distances, add or subtract accents, or place dots of color variously around the painting. The artist is thoughtfully weighing the different parts in the slowly growing mosaic. He works under the restraint of a law which he feels compelled to obey, the law of balance. It is a fundamental principle, no matter the style or type of work, so his esthetic sense forces the artist to adjust the piece to so that it will comply with his ideas of balance.

We can subject pictures to a simple test. This test works even if we take the good words by artists who have said composition doesn’t matter. Find the actual center of the picture and draw a vertical and horizontal line through it. The vertical division is the more important, as the natural balance is on the lateral sides of a central support. It will be found that the actual center of the canvas is also the actual pivot or center of the picture. Around the center point the various components of the picture will group themselves, pulling and hauling and warring for attention. The satisfactory picture showing as much design of balance on one side of the center as the other, and the picture in complete balance displays this equipoise above and below the horizontal line.

Every item in a picture has a certain positive power, as if each object were a magnet of a given strength. Each item has two characteristics. Each object has a certain amount of attraction for the eye, and it also has a proportional detraction of every other part. The more you notice an object in the picture, the less you notice anything else in the picture.

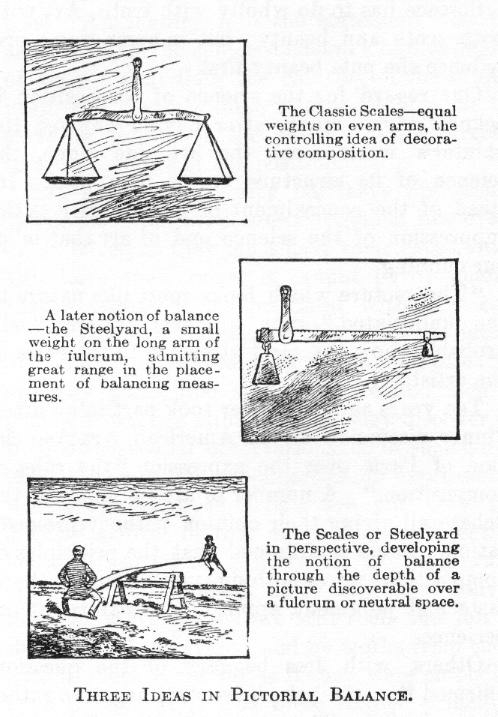

The term “Steelyard” refers to a steelyard balance. This type of balance or scale is able to use a small weight at a distance along a lever to a fulcrum to counterbalance a larger weight.

Steelyard balance

By moving the counterweight along the arm, you use the power of the lever to offset increasingly larger weights.

So for the principle of the steelyard, the farther from the center and more isolated an object is, the greater its weight or attraction.

Therefore, when using the steelyard, the balance of a picture you will find that a large object placed a short distance from the center will be balanced by a very small object on the other side of the center and further away from it. The whole of the pictorial interest may be on one side of a picture and the other side might be practically useless as far as picturesqueness or some story-telling possibility is concerned, but the purpose of its existence is only to act as the balance and for no other reason.

In the emptiness of the opposing half such a picture, when completely in balance, will have some bit of detail or accent which the eye in its circular, symmetrical inspection will catch, unconsciously, and weave into its calculation of balance. If not an object or accent or line of attraction, then some technical quality, or spiritual quality, for example, a strong feeling of gloom, or depth for penetration, light or dark, a place in fact, for the eye to dwell upon as an important part in connection with the subject proper, and recognized as such.

One may wonder, if all the subject is on one side of the center and the other side depends for its existence on a balancing space or accent only, why not cut it off? Do so. Then you will have the entire subject in one-half the space to be sure, but its harmony or balance will depend on the equipoise when pivoted in the new center.