December 25 2015

MERRY CHRISTMAS!!!

This book, Pictorial Composition and the Critical Judgment of Pictures, by Henry Rankin Poore and written in 1903 is one of the most brilliantly written books I have come across. It is a subject about which many artists lack knowledge and thus struggle with their work, simply because it was information they were never taught. Originally written, as many books from that time were, with a more eloquent and decorative speech, something many folks may find difficult to wade through. I will be attempting to translate the dialogue in the book into something you may find easier to read – hopefully without losing too much in the translation. It is a book you can find on-line or as an E-book. Some of the pictures he references in the book I will try to re-source since the scans of the original may be suboptimal to observe what he is talking about.

RECONSTRUCTION FOR CIRCULAR OBSERVATION.

Even though the original design idea may have be in the shape of a pyramid or a rectangle the end effect can be very different. A circular composition can be vertical, or once laid flat in perspective becomes an ellipse. Often the a composition is made circular not because of any arrangement of the parts, but by the sacrifice and elimination of edges and corners. The value of the circle as both a unifying and simplifying agent cannot be overestimated. Circular eye path works especially well in solving the problems which occur in composition even when the original idea wasn’t circular. When applied, the idea of a circle seems to bring a relief to confusion and disorder. In many cases where all essential items are happily arranged, but, as a whole refuse to compose, the addition of some element or the readjustment of a part which will produce circular observation, will often provide the solution to the problem.

Just as the movement and direction of a straight line will carry us quickly out of the picture, a circular progression will keep us within the edges. If we accept that circular observation affords the best means of appreciation, then it follows that circular composition is the most potent and influential form of presentation.

Listed As Gerard Dow, correctly would be Gerard Dou

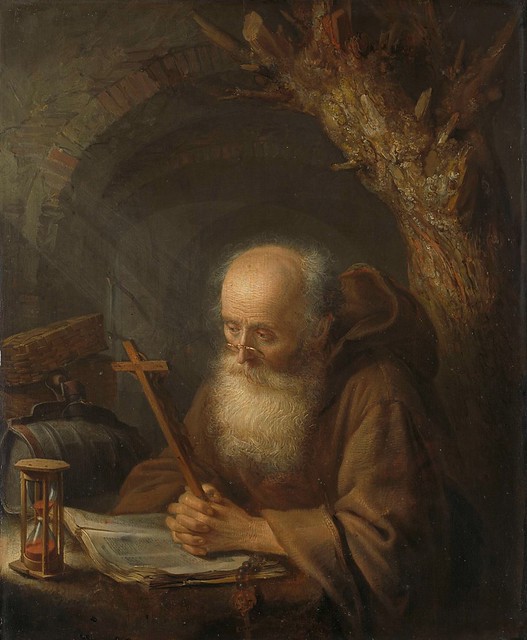

There are many subjects which naturally do not fall in these lines, but which may often be reedited into this class This reediting means composition, and two examples from a vast number are here given to show the working out of the problem. In the “Hermit,” by Dow, the figure, book and hour glass compose in a simple left angle, but the head becomes the center to a circular composition by the presence of the arch above and the encircling shadow behind and beneath the arm. The corners sacrifice their space to strengthen the center and the vision is thus completely funneled upon the head.

Gerard Dou’s painting in color

The Rectangular composition

The circular composition within the rectangular composition

There are lines within the bark helping to reinforce and continue the arc of the circular idea

There is also a vortex formed by the receding lines of the arches helping to strengthen and form a serene movement from the back ground to the center of the composition, the head.

In striking contrast to this is the composition by Boucher. Here are the elements

for two or three pictures thrown into one, and in some respects well governed as a single composition.

“Boucher Vulcan Presenting Venus with Arms for Aeneas” by François Boucher – Unknown. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Imagine this subject without the darkened corners, and the gradations which create a focus. The figures would lie upon the canvas somewhat in the shape of a letter Z, devoid of essential coherence, with the details in the foreground hopelessly exposed as padding.

Another resort in order to secure a vortex, or a center bounded by a circle, is to surround the head or figure with flying drapery, branch forms, a halo or any linear item which may serve both to cut out and to hem in. It accomplishes something of what the hand does when held as a tunnel before the eye. Such a device offers ready aid to the decorator whose figures must often receive a close encasement, fitted as they are into limited spaces, when many an ungracious line in the subject is made to disappear through the accommodation of pliant drapery or of varied tree forms.